Multiplying patterns of nature in paint: an interview with Chris Arnold

Above, Joyful Flowers by Chris Arnold

When I first saw Chris Arnold’s work, I was struck by the boldness of the graphic design of the plants and flowers within his paintings. The flowers and vegetation, expressed in different hues of viridian, sap green, and a rainbow of ochres, ultramarine, cadmiums and pinks, were packed together in pattern-like expression. In this way, his work mirrors nature; the feeling of looking out over a garden and seeing the first impression of the beauty of the flowers, then zooming in and realizing that there is also a world of beauty and detail within each flower… evenly spread out over the entire garden, multiplying endlessly. This feeling of the patterns of nature repeating in not-quite perfect replication is exactly how I feel when I look at Arnold’s work: an almost scientific celebration of the design of nature, expressed in paint. And I was able to see the work firsthand when we exhibited one of his pieces in our group show Gardens of Enchantment at the Hamptons Fine Art Fair this summer.

Above, gallery view of Chris Arnold’s work

Chris Arnold is an American artist and illustrator whose work explores the deep connections between nature, environmental awareness, and conservation. He wants his paintings to tell the story of nature by being the visual voice of animals, plants, and the environments in which they exist. Influenced by cartoonists, Impressionists, and the Art Nouveau movement, Arnold’s work blends bold, expressive forms with intricate natural elements, creating compositions that are both playful and thought-provoking. His art is a reflection of his passion for environmental consciousness, using visual storytelling to inspire curiosity and action. Whether painting in his studio, his garden or immersed in the wild, he seeks to capture the spontaneity, beauty, and resilience of the natural world.

We are delighted to offer this exclusive interview with the artist here on Era Contemporary’s substack. Below, find our questions and Arnold’s answers about his inspiration, process and how he creates his work.

Above, Flower Garden in White by Chris Arnold

Welcome Chris! Looking at your portflio, your work has evolved toward an increasing stillness—quiet landscapes, controlled light, and deep atmospheres. How has your practice changed over time, and what moments were most formative in that evolution?

Over time, my work has shifted from bold, aggressive expressions to something more measured, quieter, and more contemplative. Early in my career, I felt a strong urge to make an impact, to push outward with energy and intention. But as I’ve grown, both personally and professionally, my practice has turned inward—more attuned to subtlety, reflection, and stillness. That evolution wasn’t sudden; it emerged through lived experience, time in nature, and learning to listen more closely to the world around me. Some of the formative moments have ranged from hiking into remote landscapes of National Parks to simply painting in my own backyard. Recent time spent in traveling, especially in Europe, has deepened my understanding of place and history, offering new ways of seeing.

In “Arboretum,” the piece that was featured in the Hamptons and also, happily, sold, we sense both the presence of a place and a deliberate abstraction of it. What influences—artistic, literary, or environmental—have shaped your way of seeing?

Above, Arboretum by Chris Arnold

In Arboretum, I was influenced by the duality of natural spaces and how they can be both rooted in reality and open to abstraction. The Morton Arboretum in Chicago, where I’ve spent time observing seasonal shifts and light patterns, deeply shaped this piece. It’s a cultivated space that still carries a sense of wildness, and that contrast between structure and organic rhythm is something I love to explore in my work.

Artistically, my way of seeing has been shaped by a range of influences—from the expressive color and atmosphere of the Impressionists to the flowing lines and stylized forms of Art Nouveau, as well as the clarity and boldness found in cartooning. Each brings a different lens to how I interpret and construct an image. Literarily, my influences are wide-ranging, but books on nature and color theory play a central role in my process. They help me think about how place, mood, and palette can come together to create a visual language that’s both personal and open to interpretation.

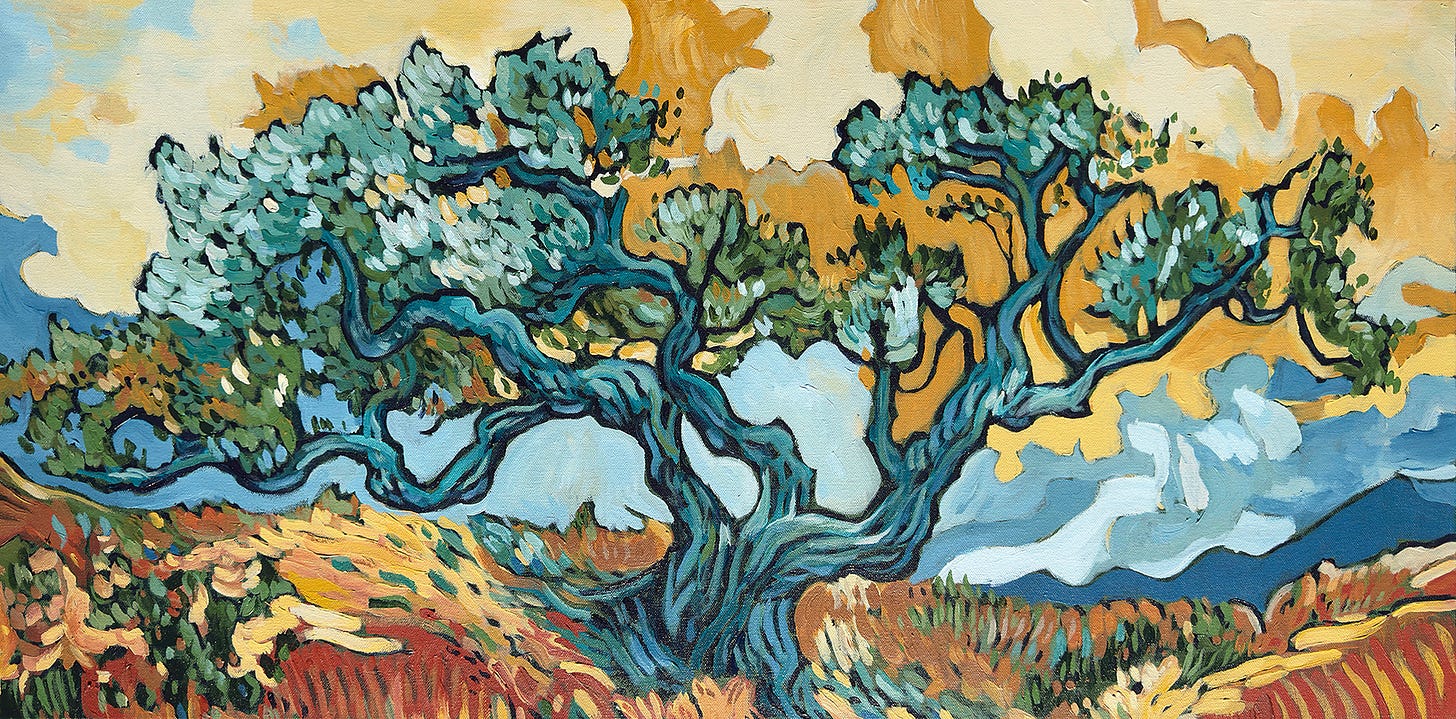

Above, Roots of Tuscany by Chris Arnold

You trained both in painting and drawing. How has your foundational focus on draftsmanship informed your current visual language?

My foundational training in painting and drawing, rooted in my BFA in Studio Art from the University of Missouri, Columbia and later refined through my MFA in Illustration from the Savannah College of Art and Design, continues to shape the way I see and build images. That early focus on draftsmanship taught me how to observe, interpret, and construct with intention. Even in my more expressive or abstracted work, a strong sense of structure and form remains beneath the surface. It allows me to take risks, knowing I have a solid foundation to return to. Whether I am working from observation or memory, that training is always guiding the composition, the layering, and the rhythm of each piece. It remains essential to how I develop and refine my current visual language.

Are there artists—historical or contemporary—who helped unlock something pivotal in your development? And do you feel in dialogue with them when you work?

There are far too many artists to recognize in the overall influence of my journey, but a few stand out as pivotal. Van Gogh’s emotional intensity and use of color helped me understand how paint can carry feeling. William Morris showed me the power of pattern and the importance of beauty in everyday life. Georgia O’Keeffe’s ability to distill form and elevate the natural world has been a constant source of inspiration. And Picasso—particularly through Guernica—opened my eyes to the potential of art to inform, provoke, and communicate beyond aesthetics.

While I don’t consciously think about these artists when I’m working, I do feel in quiet dialogue with them. Their approaches, their questions, and their boldness are always somewhere in the background, shaping the way I see and make.

Above, Summer Flowers by Chris Arnold

What drew you initially to landscape and built environments as primary subjects, and how has your relationship to them deepened with time?

I was initially drawn to landscapes and environments because they offered a sense of place—a way to ground emotion and narrative in something tangible. As someone who’s always been curious about the natural world and how we live within it, these subjects felt like an honest starting point. They allowed me to explore structure, rhythm, and atmosphere while also reflecting on memory and movement.

Over time, my relationship to these spaces has deepened. I’ve come to see them not just as settings, but as living, breathing systems but shaped by history, ecology, and human impact. Whether I’m painting a garden, a forest edge, or a more abstracted form, I’m thinking about how place holds meaning. It’s no longer just about what’s there, but how it feels, how it changes, and what it can reveal about us.

Your compositions balance structure with atmosphere—rigor with nuance. How do you make decisions in the painting process? Is it intuitive, methodical, or something in between?

My painting process lives somewhere in between intuition and method. The illustrator in me appreciates a structured approach—planning compositions, thinking about design, and building a foundation with intention. But the artist in me thrives on expression, spontaneity, and the freedom to follow where the work wants to go.

I usually begin with a clear framework, often inspired by research, observation, or place, but once I am in the painting, I allow myself room to react and respond. Layers build, forms shift, and sometimes things are added or taken away on instinct. That tension between control and release is where the most interesting moments happen. It is in that space, between structure and atmosphere, that the work feels most alive.

Above, Garden of Love and Luck by Chris Arnold

There’s often a sense of duality in your work: familiarity and strangeness, solitude and presence. How conscious is this tension, and when did it begin to appear in your paintings?

I think that sense of duality has always been present in my work, even before I had the language to articulate it. But I really began to lean into it after my Artist-in-Residence with the National Park Service. Being immersed in a wild, protected landscape brought everything into sharper focus—the tension between what feels known and what remains mysterious, between solitude and the quiet presence of life all around you. That experience made me more aware of the layered emotional and environmental complexities within a place.

It taught me to look beyond the surface and to hold space for both beauty and ambiguity in the work. Since then, I have become more intentional about exploring that balance—inviting the viewer into spaces that feel at once intimate and expansive, grounded and slightly otherworldly. That tension is not something I force, but it emerges naturally when I am fully present with the subject. It is part of how I experience the world, and the paintings have become a way to reflect that dual experience back to the viewer.

Above, Floral Happiness by Chris Arnold

Many of your works are devoid of human figures, yet feel psychologically inhabited. Have your intentions shifted over time around presence, absence, and the viewer’s role?

Yes, my intentions around presence and absence have definitely evolved over time. While many of my works are devoid of human figures, I think they’ve become increasingly focused on the emotional and psychological traces we leave behind. I’m less interested in depicting people directly and more drawn to creating spaces that feel lived in, remembered, or imagined—places where the viewer becomes the presence.

Over time, I’ve come to see the absence of figures not as emptiness, but as an invitation. It gives the viewer room to enter the work, to project their own feelings and experiences into the space. That sense of quiet presence—of something just before or just after—adds a layer of narrative tension that I really value. It allows the work to stay open, unresolved, and more personal to whoever is looking.

What does refinement mean to you as an artist—technically, emotionally, or compositionally?

Refinement, to me, is less about perfection and more about clarity—knowing what to hold onto and what to let go. Technically, it means having the skill to make deliberate choices while allowing room for the unexpected. Emotionally, it is about understanding the feeling I want to convey and making sure every element supports that intention. Compositionally, refinement is about finding balance between structure and spontaneity, detail and openness, light and shadow. It is a process of distillation, peeling back layers until what remains feels honest and essential. I do not see refinement as a final polish, but as an ongoing act of listening—to the work, the subject, and myself.

Above, Chris Arnold

If you could return to a single early painting or sketch and speak to your younger self as an artist, what would you say?

If I could return to a single early painting or sketch, I honestly wouldn’t change or tell my younger self a thing. I love my life—the good, the bad, the breakthroughs, and the missteps. Everything I have done has shaped who I am, both as a person and as an artist. Those early works were part of the journey, and without them, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I would just stand there quietly, maybe smile, and let that version of me keep going, learning, and figuring it out in real time. I wouldn’t want to give any of it up or change who I am today.

For inquiries contact eracontemporary@gmail.com or visit Chris Arnold’s website at www.chrisarnoldart.com .

Written by Aurelia Vescari for Era Contemporary. Era Contemporary exists as a platform to focus on artists at the intersection of myth and material precision, through gallery exhibitions, special events and artist interviews.